Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Basin Indicator Project

Mercury in Lake St. Clair Walleye

Authors

Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Toronto, Ontario, CanadaBackground

In 1969, the Ontario Water Resources Commission (the predecessor of the Ontario Ministry of the Environment) discovered elevated levels of mercury in sediments of the St. Clair River. Follow up monitoring of mercury in fish by government and university scientists found sufficient mercury contamination to close the fishery from southern Lake Huron to Lake Erie in 1970. The St. Clair commercial fisheries were substantial, providing about 40 small family companies with $1-2 million worth of fish per year. This became known as the “Mercury Crisis of 1970” (Hartig, 1983).

The main historic source of mercury to the river was identified as the Dow Chemical Chlor-Alkali Plant in Sarnia, Ontario which operated between 1949 and 1970. Mercury is a naturally occurring metal, familiar to most people through the use of thermometers. It is used in some industrial processes and in the manufacture of some types of electrical apparatus. At one time, mercury was widely used as an antifouling agent in paints and as a controller of fungal diseases of seeds, flower bulbs, and other vegetation. It is still used as an antimicrobial agent.

Mercury is also toxic. It is found in the environment in different chemical and physical forms, the most toxic being methylmercury. In its elemental form, mercury is not regarded as a major contaminant in water because it is almost completely insoluble in water. However, elemental mercury in sediments can be transformed by microorganisms into a form which is much more water soluble, biologically mobile, and toxic than other forms. Certain fishes have been found to accumulate mercury in their tissues at concentrations 5,000 to 50,000 times greater than in surrounding waters.

Status and Trends

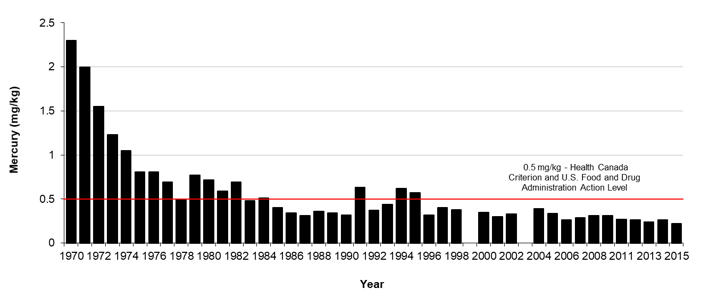

Since 1970, Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (previously called Ontario Ministry of the Environment) has systematically monitored mercury in walleye using standard sampling and analytical techniques (Figure 1). In 1970, mercury in Lake St. Clair walleye was approximately 2.3 mg/kg. That same year Dow Chemical of Canada was directed by the Ontario Water Resources Commission to install treatment facilities to eliminate mercury discharges to the St. Clair River. Later, Dow Chemical voluntarily shut down its mercury cell plants in Sarnia and Thunder Bay, Ontario (Hartig 1983). Another mercury cell plant that discharged to the Detroit River in Wyandotte, Michigan was also shut down in 1972.

Figure 1. A fourteen-pound Walleye caught in the Detroit River (Photo Credit: Jim Barta)

Authorities estimated that the effluent from the Sarnia plants ran as high as 50 mg/L at times, amounting to a release of approximately 91 metric tons of mercury into the St. Clair River, which flowed down stream to Lake St. Clair, the Detroit River and Lakes Erie and Ontario. Since the chlor-alkali plant was taken off line, Dow has spent over $75 million to control mercury sources in sewers, drains and landfills. Between 2001 and 2005, Dow remediated approximately 14,000 m3 of historically contaminated sediments in the river directly adjacent to the former Dow chemical facility at the cost of approximately $18 million USD.

A 1999 water and sediment study revealed that the current mercury distribution was quite even throughout the Detroit River, instead of the historic pockets of high concentration (Kreis et al., 2001). Mercury concentrations found in Detroit River fish were slightly lower than in the same species from Lake St. Clair. However, health advisories remain in effect for certain sizes of some fish species from both Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River. Today, the primary source of mercury is contaminated sediment from historic discharges (Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Ontario Ministry of Environment, 1991) and atmospheric loadings.

Since the elimination of mercury inputs into the St. Clair River, the mercury content in Lake St. Clair walleye has decreased more than 80% (Figure 2). Similar reductions have occurred in other fish species.

Figure 2. The concentration of mercury in 45 cm walleye in Lake St. Clair, 1970-2004 (data collected by Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks).

Management Next Steps

Control of mercury at its source is the primary imperative for action. The Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement calls for zero discharge of persistent bioaccumulative toxic substances such as mercury. Priority should be given to reducing loadings from active sources such as power plants and incinerators. Elimination of coal-fired electricity in the Province of Ontario in 2014 should contribute to recovery of the system. However, remediating mercury-contaminated sediment hot spots throughout the corridor may be necessary to make meaningful reductions in the fish mercury levels. Work is being initiated to deal with three remaining priority contaminated areas between Sarnia and Stag Island.

Research/Monitoring Needs

Monitoring of mercury in walleye should continue. Mercury isotope measurements are being performed to delineate sources of sedimentary mercury from other sources. This method can also be used to understand if historically deposited mercury is still entering the food web. Sources-fate-transport-effects modeling should be considered to evaluate further remedial options and make mid-course corrections sufficient to remove mercury related health advisories on fish from the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, Detroit River, and Lake Erie.

References

- Hartig, J. H. 1983. Lake St. Clair: Since the Mercury Crisis. Water Spectrum, 15(1), pp. 18-25.

- Kreis, R.G. Jr., G.D. Haffner and M. Tomczak. 2001. Contaminants in Water and Sediments. State of the Strait: Status and Trends of the Detroit River Ecosystem. University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Ontario Ministry of Environment. 1991. Stage 1 Remedial Action Plan for the Detroit River. Lansing and Sarnia, Ontario, Canada.