Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Basin Indicator Project

West Nile Virus in Michigan

Background

West Nile virus is a mosquito-transmitted disease that was first discovered in the African country of Uganda in 1937 (Michigan Department of Community Health 2006a). It is considered an "Emerging Infectious Disease" because of the spread beyond its traditional geographic range. In recent years West Nile virus has caused illness in birds, horses, and humans in Europe, and now the United States. It was first discovered in the U.S. in 1999 in New York City. Since that time, West Nile virus has been detected in humans, animals, and mosquitoes in 47 states from coast to coast.

West Nile virus is a disease of birds that can cause illness in humans when they are bitten by an infected mosquito. Most humans infected with West Nile virus develop no symptoms of illness, however about 20% may become sick with a fever, headache and body aches three to 14 days after receiving a bite from an infected mosquito. Rarely, persons infected with West Nile virus may develop more severe disease, including encephalitis and sometimes death.

Individuals with fever and signs of encephalitis and/or meningitis during the mosquito season should be tested for West Nile virus. Symptoms of encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and meningitis (inflammation of the spinal cord and brain linings) include severe headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, muscle weakness, convulsions and paralysis. West Nile virus is spread almost exclusively to humans by mosquitoes of the genus Culex, which are commonly found in urban environments, and lay their eggs in stagnant water that is rich in organic matter.

West Nile virus also causes severe illness and death in horses and birds. However, an effective vaccine has been developed for West Nile virus in horses.

Status and Trends

In response to the threat of West Nile virus in Michigan, the West Nile Virus Working Group, a multi-agency work group, emerged from the Arbovirus Core Group in 2000 (Michigan Department of Community Health 2006b). In 2001, a toll-free hot line was established for citizens to report dead crows, as monitoring death amongst these birds can be an early indicator of virus activity in an area.

Cases of avian West Nile virus may be an early indicator of human disease in a geographic area. Figure 1 represents positive avian samples (bars) and confirmed human case onset (line) from March to November 2005. The Michigan Department of Community Health continues to collect corvid (crows, blue jays, ravens) samples from those areas conducting surveillance.

Figure 1. West Nile virus in people and birds in Michigan, 2005 (data collected by Michigan Department of Community Health). Avian infection peaks during the second half of August, followed by the human infection peak in early September. Human and avian infections drop off quickly and are 0 by early November.

As a result of this effort, West Nile virus was first detected in Michigan in August 2001 in dead crows. There were 65 West Nile virus-positive birds detected in 10 counties including Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Washtenaw, Jackson, Calhoun, Ingham, Barry, Ottawa, and Muskegon. In addition, two West Nile virus positive mosquito pools were detected in Oakland County and one in Macomb County.

Human illness due to West Nile virus in Michigan was first documented in 2002, when a large-scale outbreak occurred in the Upper Midwest. Human cases were heralded by a massive die-off in resident corvid (crows, blue jays, ravens) populations. From early May to late October 2002, the Michigan Department of Community Health received over 10,000 reports of dead birds from the public. Southeast Michigan (including Wayne, Macomb, and Oakland Counties) was particularly hard hit, accounting for 531 of 644 statewide human West Nile virus illnesses confirmed by public health authorities. Wayne County confirmed 203 human cases, and 15 deaths, due to West Nile virus in 2002.

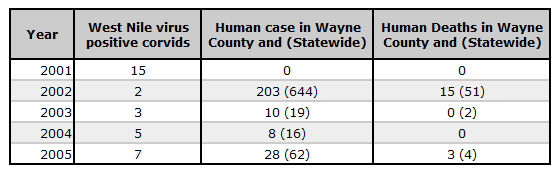

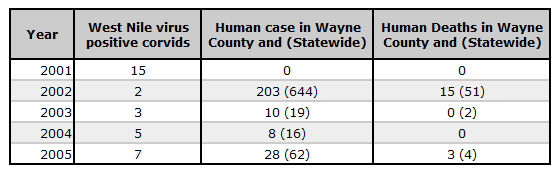

Table 1. Data on West Nile virus-positive corvids, human cases (positive for West Nile virus), and human deaths for West Nile virus from Wayne County. As noted above the first West Nile virus-positive corvid was reported in Wayne County in 2001 and the first human death attributed to West Nile virus in Wayne County was reported in 2002. Human death due to West Nile virus in Wayne County has been reported in 2002 and 2005.

Mosquito Management

Mosquito surveillance for West Nile virus has been conducted in Michigan since 2001. In 2005, over 5,000 mosquito pools were tested for the virus, and 55 pools were found to be positive. Virus activity within the mosquito population peaked quickly in late July (Figure 2), although the mosquitoes were active prior to this peak. It is likely that by controlling the early breeding populations of these mosquitoes, they can be kept at a level at which the virus will not "amplify" to critical levels, and therefore reduce the risk to humans.Culex species mosquitoes are tested for West Nile virus when local jurisdictions conduct mosquito surveillance. In southeast Michigan, mosquito infection with West Nile (bars) was documented in late July with human cases (line) following 1-3 weeks later (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Culex species mosquito infection rate versus human West Nile virus onset in southeast Michigan, 2005. Human onset and peak follows the mosquito infection onset and peak by 1 to 3 weeks. Mosquito infection peaks early in August and drops off in mid-September; human infection peaks at the end of August and drops to 0 by early October.

There are many species of mosquito in Michigan, and some are more "competent" at transmitting West Nile virus than others. In the eastern United States, the primary vectors are within the genus Culex. These mosquitoes are active in the summer, and peak biting times are dusk and dawn. These mosquitoes are also more common in urban environments, where they reproduce readily in man-made containers containing nutrient rich water. These habitats may include: sewer catch basins, bird feeders, unused swimming pools, scrap tires, or practically any other man-made container.

Since it is unfeasible to control the virus within wild bird populations, our best target for control is the mosquito. The use of licensed "larvicides" which kill the immature mosquitoes in the water have been shown to reduce mosquito populations and disease risk when used within an integrated mosquito management program. It is unlikely that individual treatment by citizens in a piecemeal fashion will reduce the risk, because mosquitoes can breed nearby in areas that are untreated.

The mosquito management program would also include: source reduction, personal protection education, and surveillance for mosquito density and virus activity.

Management Next Steps

The Michigan Department of Community Health considers West Nile virus an emerging disease issue and has devoted considerable resources to surveillance, management, and public education. No human vaccine against West Nile virus is currently available. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006) recommend the following:

- Education about reducing the risk of infection is important for all persons in transmission areas, but especially in the higher-risk populations (persons more than 50 years old and persons who are immunocompromised).

- The primary prevention step recommended is the use of mosquito repellent when outdoors. Mosquitoes may bite through thin clothing, so spraying clothes with repellent containing permethrin or another U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-registered repellent will give extra protection. These repellents are the most effective and the most studied.

- Repellents containing permethrin are not approved for direct application on the skin. Repellent should not be sprayed on the skin under clothing. Other options include wearing protective clothing (long sleeves, socks, and long pants) when outdoors. The primary mosquito-biting hours for many of the species that are important vectors of West Nile virus are dusk and dawn. It is advisable to either stay indoors during these hours or use protective clothing and repellent.

- Household mosquito-source reduction is also important. Standing water should be removed from outdoor receptacles.

- Integrated mosquito management can be another important factor in controlling mosquito populations.

Research/Monitoring Needs

Testing will continue to be conducted by Michigan Department of Community Health in order to provide community-based information about West Nile virus activity in birds and mosquitoes. The State of Michigan compiles surveillance information on the "Emerging Diseases" website, which can be viewed at: www.michigan.gov/westnilevirus

The public can also report sick or dead birds on the above website. Michigan Department of Community Health then makes a determination as to whether or not a bird should be tested for West Nile virus. Michigan health workers are implementing a system of animal and human disease surveillance that utilizes geographic information system mapping capabilities to detect outbreaks more rapidly. Communities can use the West Nile virus surveillance data to help target their intervention and prevention strategies to areas where West Nile virus activity has been detected. Research continues on a possible human vaccine and health treatment options.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006. Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Disease: West Nile Virus Prevention. (May 2006).

- Michigan Department of Community Health. 2006a. Emerging Disease Issues: History of West Nile Virus. (May 2006).

- Michigan Department of Community Health. 2006b. Emerging Disease Issues: West Nile Virus Working Group. (May 2006).

Contact Information regarding West Nile Virus in Michigan

Erik S. Foster

Wildlife and Vector Ecologist/BiologistMichigan Department of Community Health

Division of Communicable Disease

E-mail: fostere@michigan.gov