Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Basin Indicator Project

Lead Poisoning in Detroit, Michigan

Authors

Lyke Thompson, Director, Center for Urban Studies, Wayne State University, lykethompson@gmail.comLauren Meloche, Research Assistant, Center for Urban Studies, Wayne State University, as2271@wayne.edu

Background

Lead is a highly toxic metal that causes significant adverse health outcomes. Despite lead’s toxic characteristics, it has been used for centuries in products such as paint, gasoline, ceramics, pipes, batteries, cosmetics, toys, and pesticides. The presence of lead hazards in our environment resulting from these uses creates a problem that it is still considered a major public health concern.

Lead enters the body through swallowing or breathing lead particles and can then accumulate in the blood, tissues, and organs. The amount of lead in blood is referred to as blood lead level (BLL) and is measured in micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (μg/dL). Any amount greater than 5µg/dL is considered an elevated blood lead level (EBLL), a reference point set by the Center for Disease Control (CDC). However, there is no known safe blood lead level, and irreversible health damage can occur at BLLs below 5µg/dL (CDC 2012).

Figure 1. Deteriorated lead-based paint is one of the leading causes of lead poisoning in Detroit children (Photo Credit: Luciano Sanchez).

Exposure to lead has serious neurological and behavioral consequences, particularly for children. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (2005), the best studied effects of lead poisoning are cognitive impairments measured by IQ tests, but other aspects of brain or nerve function, especially behavior, may also be affected. Students with elevated lead levels are found to be hyperactive, disorganized, less attentive, and have difficulty following directions. Other consequences of lead poisoning are motor development delays, impaired growth, and hearing dysfunction. Beyond effects on cognitive function, lead can produce negative cardiovascular, immunological, and endocrine effects (CDC, 2012). According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), health consequences of lead poisoning can also have physical symptoms such as headaches, stomachaches, sleeping or eating disorders, attention deficit disorders, and weakness or clumsiness. Even where physical symptoms are not present, there can be significant health damage.

Children under age six are especially vulnerable to lead poisoning (ATSDR, 2007). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the CDC National Center for Health Statistics reported that 2.6% of children between ages one and five had elevated blood lead levels (EBLLs) of 5µg/dL. This translates to approximately half a million lead poisoned children nationwide.

Status and Trends

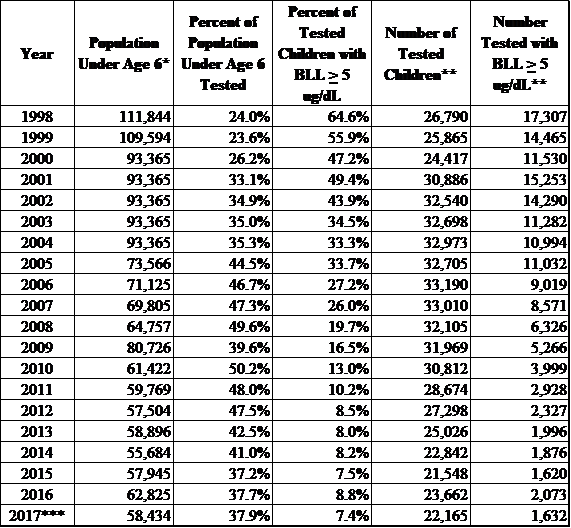

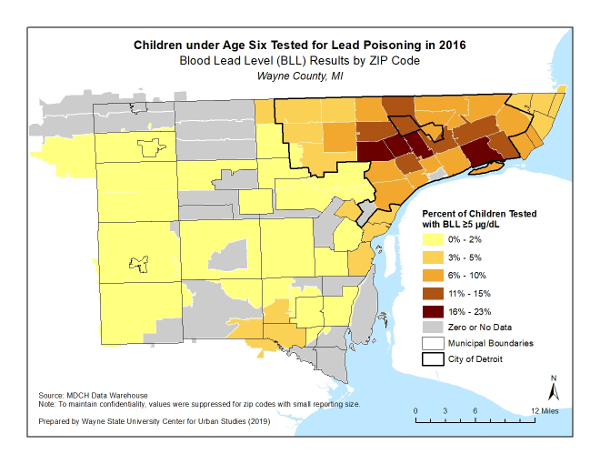

In the City of Detroit during 2016, 2,073 children under six years old (8.8%) were tested for lead poisoning and found to have elevated blood lead levels (BLL) at or above 5ug/dL (MDHHS, 2018). Fewer than half (40.4%) of all Detroit children under six were tested, so it is unknown how many of the 34,903 untested children also have elevated blood lead levels. As shown in Table 1, the number of tested children with elevated BLL increased by 27.9% in 2016 compared to 2015. This was the first year since 2005 that the number of tested children with BLL at or above 5ug/dL increased compared to the prior year. Provisional data for 2017 show that 1,632 children were found to have an elevated BLL, equivalent to 7.4% of the children tested. Although fewer than in 2016, this is still slightly higher than the 1,620 children with EBLLs identified in 2015. The persistently high number of children found to have elevated BLL and the recent spike in tested children with lead poisoning signal that lead hazards still pose a significant danger to Detroit’s children.

Table 1. Lead poisoning statistics for children under age six living in Detroit, MI, 1998-2017.

Note: BLL = blood lead levels. Reflects capillary tests, venous tests, and unknown.

*Source: Michigan Information Center, Population Estimate by Single Year of Age for Michigan and Counties (years 1998-1999); U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census (years 2000-2004); U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-year estimates (years 2004-2017)

**Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program annual reports

*** Data for 2017 are provisional.

Note: BLL = blood lead levels. Reflects capillary tests, venous tests, and unknown.

*Source: Michigan Information Center, Population Estimate by Single Year of Age for Michigan and Counties (years 1998-1999); U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census (years 2000-2004); U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-year estimates (years 2004-2017)

**Source: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program annual reports

*** Data for 2017 are provisional.

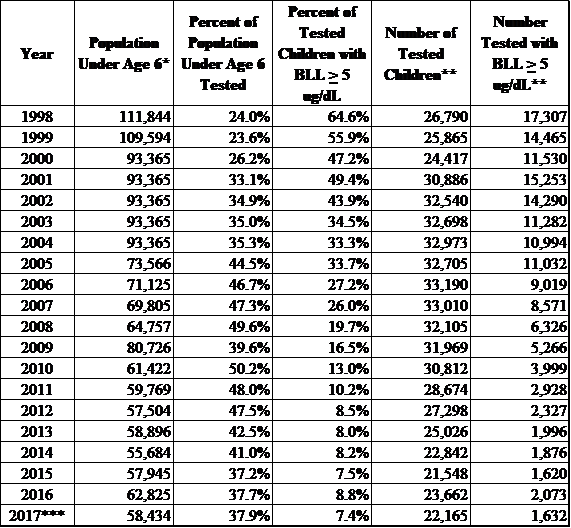

The true extent of childhood lead poisoning in Detroit remains unknown as a result of low testing rates. Despite efforts to increase regular lead screening among children in Detroit, fewer than half of children under age six are tested for BLL each year, as shown in Figure 2. The proportion of tested children with elevated BLLs has declined substantially from a high incidence rate of 64.6% in 1998, the first year that monitoring data were available. However, the proportion of tested children with an EBLL sharply increased in 2016 compared to the prior year, following several years where the annual rate of decline had leveled out. Although provisional numbers for 2017 show a reduction compared to the prior year, the number of tested children with an EBLL is still higher than 2015 numbers, and the proportion of tested children with an EBLL is only 0.1% lower than the corresponding rate for 2015.

Figure 2. Longitudinal trends of lead poisoning of children under age six living in Detroit, MI, 1998-2017

Sources: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program annual reports; Michigan Information Center, Population Estimate by Single Year of Age for Michigan and Counties (years 1998-1999); U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 Census (years 2000-2004); U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 1-year estimates (years 2004-2017)

Note: Data for 2017 are provisional.

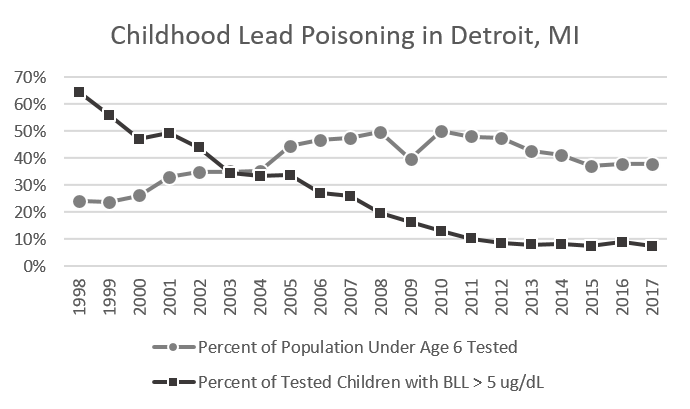

Across Wayne County each year between 2011 and 2016, Detroit zip codes consistently reported the highest numbers of tested children with elevated blood lead levels. The Detroit zip codes with the highest rates of childhood lead poisoning in 2016 are shown in in Figure 3. In 2016, zip code 48206 in central Detroit had the highest proportion of lead poisoned children, with 22.2% of tested children having EBLLs >= 5mg/dL. Provisional data for 2017 indicate zip code 48206 ranked highest again, with 19.2% of tested children having an EBLL. Zip Code 48206 also ranked highest each year from 2011 through 2014. In 2015, zip code 48206 shared the t hird rank with neighboring 48202, both having a rate of 13.9% that year. Provisional data show that 48202 also ranked third in 2017, with 13.5% of tested children having EBLLs. Zip code 48214 on Detroit’s east side has ranked in the top three zip codes each year between 2011 and 2016, having the highest rate of lead poisoned children in 2015 (17.2%) and the second highest rate in 2016 (16.4%). Provisional data for 2017 shows zip code 48214 continues to rank second highest, with 16.1% of tested children having an EBLL. Zip code 48204 ranked fourth highest in 2016 (15.1%) and kept that ranking in 2017 according to preliminary data.

Figure 3. Map of Childhood Lead Poisoning in Wayne County Zip Codes, 2016

Several sources of lead have contributed to contamination and childhood lead poisoning in the City of Detroit. These sources include:

- Lead-based paint that is deteriorated or poorly maintained, creating paint chips or dust (Figure 1);

- Lead dust that has been washed into the soil from houses during rainfall;

- Lead dust from demolitions has been spread across neighborhoods;

- Lead dust from leaded gasoline is still present in soil samples across the area;

- Contaminated soil around former smelters located at or near residential areas that have released lead into the air during operations, which has now deposited on the soil;

- Food and liquids stored in lead crystal or lead-glazed pottery;

- Water that runs in lead plumbing; and

- Automotive emissions absorbed from leaded gasoline, in use before 1986.

As lead paint is often found inside and outside of houses and apartments in the city, young children are at risk of becoming lead poisoned by swallowing paint chips and inhaling lead dust. Given that lead-based paint was used outdoors as well as indoors, lead dust can also wash off to the soil surrounding a home and poison a child during play. Children under three years of age are most susceptible to being exposed to lead because they crawl and play on floors where paint chips and dust are deposited.

Other important sources of lead contamination in the City of Detroit are former sites of lead smelters, foundries, and alloy makers in certain residential areas. It is at such former smelter sites where both adults and children have been exposed to long-term emissions of lead dust that settled in the soil around the industrial site and the surrounding neighborhoods.

Although exposure to lead from ceramics and the past use of leaded gasoline are not currently considered major sources of lead poisoning in Detroit, they are factors that must be considered. Lead was added to gasoline as a fuel additive to improve engine performance and octane ratings in the 1920s. It was phased out by government order, for public health reasons, starting in 1975 and concluding in 1986, resulting in a direct correlation with drops in elevated blood lead levels nationwide (Kovarik, 2003). An issue of concern in Southwest Detroit is the use of bean pots among residents of this community because some dishes and clay cookware contain high levels of lead in their glaze or decoration. Their use provides a direct and dangerous source of lead poisoning.

Water that runs through pipes that contain lead is another potential source of lead exposure in homes where the old lead plumbing materials have not been replaced. As many as 125,000 Detroit homes are reported to have water lines that may contain some lead. City officials have long added chemicals to Detroit’s water that produce a liner to water pipes that is intended to contain any lead in the lines and keep it out of drinking water. The action level for lead levels in drinking water is set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as 0.015 mg/L (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2005). However, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality will set a stricter standard of 0.012 mg/L, which will take effect in 2025. Plumbing systems that may contribute lead to the household drinking water supply have been systematically tested since 1992. Each year since 1992, a small number of homes are selected for water sampling to monitor lead levels in the municipal water system. However, the sampling strategy used for these monitoring activities is insufficient for individual households to draw conclusions about their risk of lead exposure through drinking water, particularly because the plumbing materials used in the interior of a home can substantially contribute that household’s risk of lead-contaminated water.

Management Next Steps

Given the various sources of lead which contribute greatly to the number of children with lead poisoning, efforts are being made by health, government, non-profit, and community development organizations to prevent and respond to lead poisoning in the City of Detroit.

Primary prevention efforts are essential to reducing the number of children who become lead poisoned. Primary prevention focuses on identifying and removing lead hazards like lead-based paint and plumbing materials. These prevention activities include:

- Abatement (permanent removal) of lead hazard sources, where possible (i.e., replacement of components or fixtures that contain lead or are painted with lead-based paint, removal of contaminated soil, washing lead dust off of items and surfaces that are contaminated).

- Where permanent abatement is not possible, temporarily removing or reducing lead hazards through the use of interim controls (i.e., enclosure or encapsulation of lead-based paint to prevent dust or chipping, covering lead-contaminated soil, use of water filters, relocating residents to locations with lower risk of exposure to lead hazards).

- The City has passed and is now enforcing provisions to its Property Maintenance Code that require landlords to first test and then eliminate lead from rental properties using either abatement or interim control or both sets of techniques.

- CLEARCorps Detroit is experimenting with relocating children and their families from homes with lead to others that have been abated or were built after 1978.

- All inspection, testing, preparation, cleanup, disposal, and post-abatement clearance testing activities associated with such abatement or interim control measures.

At the state level, the Child Lead Exposure Elimination Commission (CLEEC) was established in 2017 to coordinate long-term strategies for eliminating childhood lead poisoning in Michigan, building upon the work of previous commissions. CLEEC produced a five-year Action Plan in 2018, with a focus on recommendations for primary prevention. This includes identifying lead in homes before children are poisoned and abating those hazards. Enhanced testing is a main focus of the Action Plan, with recommendations for universal BLL testing for children under 36 months of age, as well as expanded soil and water testing. Action Plan recommendations also include expanding public education efforts, adopting a statewide housing code enforcement model, improving data collection, and using data to inform activities and better target prevention efforts. At a policy level, CLEEC recommends requiring lead inspection and risk assessments for high-risk rental housing, childcare and adult care facilities, and residential properties built before 1978 in advance of their sale or lease. Additionally, CLEEC suggests updating policies related to landlord penalties, household action limits for water, and certification for contractors seeking a building or renovation permit for a pre-1978 home. The successful implementation of the Action Plan will rely on the availability of sustainable funding sources to carry out these recommendations.

Research/Monitoring Needs

Continued research and monitoring are warranted to track this key indicator of children’s health in order to minimize childhood exposure to lead. Wayne State University’s Center for Urban Studies suggests that research should continue to focus on ways to target funding for testing, abatement, relocation, and prevention, and also to identify which programs will contribute to reductions in lead poisoning more efficiently and effectively. Further research is also warranted on human health effects of lead poisoning. Such human health research, coupled with childhood monitoring and mitigation of lead exposure, must be sustained until childhood lead exposure in Detroit is no longer considered a threat.

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). 2007. Toxicological profile for Lead. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. (https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp.asp?id=96&tid=22).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. 2005. Lead Exposure in Children: Prevention, Detection and Management. Policy Statement. Vol. 116, No. 4: 1036-1046. http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;116/4/1036).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2016. Childhood Lead Poisoning Data, Statistics, and Surveillance. (https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/data/index.htm).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2012. Low level lead exposure harms children: a renewed call for primary prevention: report of the Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. (https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/ACCLPP/Final_Document_030712.pdf)

- Childhood Lead Exposure Elimination Commission. 2018. 2018 Annual Report. (https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdhhs/2018_CLEEC_Annual_Report_-_FINAL_642077_7.pdf).

- Detroit Water and Sewage Department. 2004. Water Quality Report. (http://www.dwsd.org/cust/wqr_2004.pdf).

- Kovarik, W. 2003. The Ethyl War, Forbidden Fuel and Public Poison, The Ethyl War Summary: Leaded Gasoline History and Current Situation (http://www.radford.edu/~wkovanik/ethylwar).

- Lam. T. and W. Wendlandbowyer. 2003a. Potential of danger at 16 sites brings little action. Detroit Free Press (http://www.freep.com/news/childrenfirst/Lead7_2003407/htm).

- Lam, T. and W. Wendlandbowyer. 2003b. Old sites forgotten, ignored. Detroit Free Press (http://www.freep.com/news/childrenfirst/Lead7_2003407/htm).

- Lewis, J. 1985. Lead Poisoning: A Historical Perspective. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, D.C.

- Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). 2018. Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program annual reports. (https://www.michigan.gov/lead/0,5417,7-310-84214---,00.html).

- Raymond J, Brown MJ. 2017. Childhood Blood Lead Levels in Children Aged under 5 Years — United States, 2009–2014. MMWR Surveillance Summary 2017; 66(No. SS-3):1–10. (http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6603a1).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2005. Drinking Water Contaminants and Maximum Contaminant Levels (http://www.epa.gov/safewater/mcl.html%232).

- Wayne State University (WSU). 2003. Lead Poisoning Research at the Center for Urban Studies. Detroit, Michigan. (http://www.detroitleaddata.cus.wayne.edu/).