Detroit River-Western Lake Erie Basin Indicator Project

Soft Shoreline Along the Canadian Side of the Detroit River

Authors

C. Sanders, Detroit River Canadian CleanupBackground

The Detroit River, a 51km connecting channel, flows south from Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie, and is part of the international boundary that separates Canada from the United States. The river drains all or part of six municipalities in Canada and flows past the City of Windsor, the Town of LaSalle and the Town of Amherstburg. Historically, the abundant natural resources within the Detroit River watershed provided an oasis for fish and wildlife. Over the last century, the river and its watersheds became a prime settlement site and an active transportation, industrial and recreational corridor. The Detroit River has experienced remarkable industrial development over the last 100 years. With this development came widespread pollution and a significant loss of coastal wetlands, as well as degradation of habitat and water quality. As the communities in the river’s watershed grew on both sides of the border, this degradation continued without responsible environmental management. Intensive urban and industrial development along the shoreline led to shoreline hardening and other alterations that affect fish habitat, shoreline processes and water quality (Nodwell et al., 2007). This contributed to the designation of the Detroit River as an Area of Concern (AOC) in a Protocol to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1987.

Loss of fish and wildlife habitat is one of the 14 impaired uses identified in the Detroit River remedial action plan (RAP). The Stage 1 report noted that “a significant loss of fish and wildlife habitat and, in particular, wetlands in the Detroit River AOC has occurred as a result of a number of factors, including poor substrate quality, diking, dredging, the construction of bulkheads and filling” (Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Ontario Ministry of the Environment, 1991).

Delisting criteria for the Canadian side of the Detroit River for the loss of habitat beneficial use impairment was identified in the Stage 2 report under the following four categories: aquatic and riparian habitat, shoreline softening, terrestrial habitat, and coastal wetlands. The delisting criteria for shoreline softening and coastal wetlands in the RAP Stage 2 document states: Develop and begin to implement a shoreline management strategy to soften and naturalize Detroit River Canadian shoreline, whenever opportunities arise.

Hard shorelines, characterized by concrete breakwaters or steel sheet piling, were commonly engineered along both the U.S. and Canadian side of the Detroit River in the early 20th century to protect from erosion, flooding, and to accommodate industry and ship navigation (Hartig and Bennion, 2017). Previous shoreline assessments suggest that more than 80% of the entire Canadian and US shoreline combined is developed and artificially hardened as a result of urbanization and industrialization which has degraded habitat for many fish species.

Since the establishment of the RAP, soft shoreline engineering, which is the process of using rocks, vegetation and other materials to improve the ecological features in the land-water interface, has been championed as a remedial action under the loss of fish and wildlife beneficial use impairment. Unlike a steel breakwater and other ‘hard’ structures, which impede the growth of plants, soft shorelines, also known as living or green shorelines, grow over time. These more natural infrastructure solutions provide wildlife habitat, as well as protection and resilience to communities near the waterfront. It has proven to be an innovative and cost-effective technique for shoreline management (ERCA, 2014). To date, a total of 53 soft shoreline engineering projects have taken place along the Canadian and American Detroit River and Western Lake Erie shorelines (Hartig et al., in press). Most of these projects were opportunistic and based on erosion control priorities. The DRCC Stage 2 report recognized that a strategic approach is required to identify areas that can be softened on a proactive basis.

The 2012 Detroit River Shoreline Assessment revealed the primary land uses along the river as: Commercial (5%), Park (19%), Natural (21%), Industrial (12%), Residential (38%), Other (5%). Since public funding availability and support for habitat creation varies for each of these land uses, different communications strategies are required to engage residential landowners vs. municipal or industrial landowners. Furthermore, a long-term strategy to support Detroit River municipalities in adopting this infrastructure technique will be required to ensure long-term sustainability.

The DRCC Stage 2 also notes that a management strategy should follow an ecosystem approach to habitat conservation and recommends that shoreline softening projects should be integrated with habitat enhancements on the land and in the water (i.e. in conjunction with possible wetland creation and riparian buffers). Therefore, this strategy must also consider what opportunities have already been identified for enhancing or creating hydrologically connected wetlands and riparian buffer areas around coastal wetlands through the Essex Region Natural Heritage Systems Strategy (ERNHSS).

2012 Shoreline Assessment

The Detroit River Canadian shoreline includes approximately 1,000 public and private mainland properties (ERCA, 2012). As part of the Detroit River Shoreline Assessment Project, each property along the Canadian side of the Detroit River was visited and details related to the sites’ biological and structural characteristics (e.g., natural, sheet steel wall, etc.) were collected. This information was analyzed and mapped. Opportunities for restoration were classified to identify and prioritize areas for shoreline restoration or enhancement. Site specific restoration opportunities are now being developed.

Shoreline Changes Over Time

The Lake Erie Biodiversity Conservation Strategy (LEBCS; Pearsall et al., 2012), funded by US EPA’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and Environment Canada, aims to facilitate coordination of actions among partners, providing a common vision for conservation of Lake Erie. The LEBCS endeavours to set ecosystem objectives and establish targets, including targets for Lake Erie connecting channels (Huron-Erie Corridor and Upper Niagara River). While the LEBCS was never 8 officially adopted by the Lake Erie LAMP, the Lake Erie Partnership Management Committee officially endorsed the critical threats identified in the LEBCS (Luca Cargnelli, pers. comm. 2018).

The LEBCS establishes soft shoreline habitat quality targets for the Lake Erie connecting channels (Detroit River, St Clair River, and Upper Niagara River), which are recommended to provide critical habitat for the full diversity of native species. These targets are:

- Less than 60% soft shoreline = poor quality

- 60%-70% soft shoreline = fair quality

- 70-80% soft shoreline = good quality

- Greater than 80% soft shoreline = very good quality

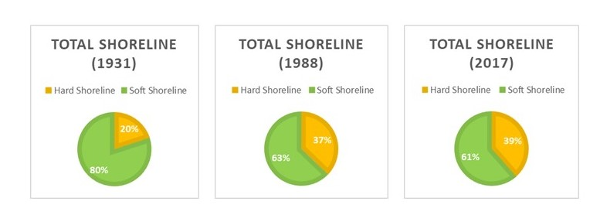

An evaluation and summary of the historical loss and current shoreline rehabilitation efforts along the Canadian side of the Detroit River outlines the current state of efforts in the AOC and provide trends of shoreline rehabilitation against quantitative targets. This evaluation was done using a comparison of the 1931, 1988 and 2017 georeferenced aerial imagery, and is based on the Hartig and Bennion (2017) study. For the entire Canadian shoreline of the Detroit River, currently 39% of the shoreline was identified as ‘hard’ (Figure 1). The 61% soft shoreline places it just inside the LEBCS ‘fair’ indicator category noted above. In order to reach a ‘good’ rating, an additional 5.04 km of shoreline would need to be softened. To reach a ‘very good’ rating, an additional 10.96 km needs to be ‘softened’ along the length of the river. In addition, despite the on-going effort of the RAP and the ten projects undertaken along the shoreline, this analysis shows that the trend towards shoreline hardening has not been reversed since the establishment of the RAP. If the trend continues, losing less than a kilometer of soft shoreline will place it in the ‘poor’ habitat quality category as established by the LEBCS.

Figure 1. Percentage of hard vs. soft shoreline in 1931, 1988, and 2017.

It should also be noted that a strict assessment of hard vs. soft shoreline does not take into consideration habitat quality and values associated with associated substrate and vegetation. In several of the priority restoration opportunities noted below, the shoreline is technically ‘soft’ with rubble, concrete, or limestone rip-rap. As noted in Hartig and Bennion (2017), while this incidental habitat and rip-rap are superior to sheet steel piling, opportunities may still exist to remove the rubble, and pull back to the shoreline to create more gradual slopes with undulating shorelines. Pre- and post- monitoring of emergent and submerged vegetation, fish assemblages, invertebrates, and amphibians at these sites can help to fully document ecological results and allow adjustments to management actions.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Over the past 32 years, considerable habitat restoration has occurred in and along the Detroit River. Despite this progress, more work is needed to meet long-term ecological goals. This is emphasized by the knowledge that, despite intentional effort and 10 shoreline projects undertaken through the remedial action plan, the ‘hardening’ trend has not been reversed along the Canadian side of the Detroit River. For long-term sustainability, the habitat priorities of the RAP need to be reflected in Official Plans and other regional policies and funding made available to support landowners who choose more ecologically-friendly shoreline options. To make further gains in natural shoreline, implementing a program that provides funding to private landowners to support up to 50% of the project costs should be considered. As with other landowner stewardship programs, the Conservation Authority would be able to administer this type of program but federal and/or provincial funding would be required to implement it.

There has been progress in reversing the loss of coastal wetlands in the corridor since the start of the RAP. Policy and long-term ecological goals for improving wetland function in the AOC should align with the ERNHSS and the strategic directions outlined in the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s guiding document A Wetland Conservation Strategy 2017- 17 2030. Developing targets for improving wetland function, particularly for the Canard River complex, should continue to be a priority for the RAP.

After the completion of the new bridges, and as management tools become available for Phragmites and urban waterfront redevelopment progresses, it will be important to be opportunistic in ensuring landowners and municipalities understand the benefits of shoreline and wetland restoration. Finally, additional pre- and post-monitoring at these sites would be useful to fully document ecological results and allow adjustments to management actions (Hartig et al., 2011).

References

- Essex Region Conservation Authority. 2014. Detroit River Canadian Shoreline Restoration Alternatives Selection Manual. Essex, Ontario.

- Essex Region Conservation Authority. 2012. Detroit River Shoreline Assessment Report. Essex, Ontario.

- Hartig, J.H., C. E. Sanders, R.J.H. Wyma, J.C. Boase, and E.F. Roseman. (In press). Habitat rehabilitation in the Detroit River Area of Concern. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management Society.

- Hartig, J.H. and D. Bennion 2017. Historical loss and current rehabilitation of shoreline habitat along an urban-industrial river – Detroit River, Michigan, USA. Sustainability. 9:828.

- Hartig, J.H., Zarull, M.A. and A. Cook. 2011. Soft shoreline engineering survey of ecological effectiveness. Ecological Engineering. 37: 1231–1238.

- Manny, B.A. 2003. Setting priorities for conserving and rehabilitating Detroit River habitats. In Honoring Our Detroit River: Caring for Our Home; Hartig, J.H., Ed.; Cranbrook Institute of Science: Bloomfield Hills, MI, USA, 2003; pp. 79–90.

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) and Ontario Ministry of the Environment (OMOE). 1991. Stage 1 Remedial Action Plan for Detroit River Area of Concern. June 3, 1991.

- Nodwell, A., Kyba, S. and M. Loewen. 2007. St Clair River Restoration Assessment Project Report. St. Clair Region Conservation Authority. Strathroy, Ontario.

- Pearsall, D., P. Carton de Grammont, C. Cavalieri , C. Chu, P. Doran, L. Elbing, D. Ewert, K. Hall, M. Herbert, M. Khoury, D. Kraus, S. Mysorekar, J. Paskus and A. Sasson 2012. Returning to a Healthy Lake: Lake Erie Biodiversity Conservation Strategy. Technical Report. A joint publication 19 of The Nature Conservancy, Nature Conservancy of Canada, and Michigan Natural Features Inventory. 340 pp. with Appendices.